This month, new festival Beyond The Valley came under fire for its co-opting of Native American imagery into posters, promo material and even actual festival real estate. The festival apologized for its appropriation of such imagery after much backlash on social media, in the same week Meredith Music Festival effectively banned punters from wearing feathered ‘war bonnet’ headdresses that have become standard festival attire in recent years.

That Australia’s festival-going public have woken up to the gross inappropriateness of co-opting sacred cultural relics into mass-produced, commercialised fashion statements is great – a quick walk around the Splendour In The Grass site this year was like wandering through a Navajo fashion parade, such was the ubiquity of feathered headwear – but for all the social media grandstanding against Beyond The Valley this week, the Phillip Island event is far from the first Australian festival to co-opt images and customs of other cultures for profit. Australia’s biggest music festivals have a strong recent history of regularly and blatantly appropriating the sacred symbols, traditions and customs of foreign cultures without the slightest whiff of social media outrage.

SOUNDWAVE

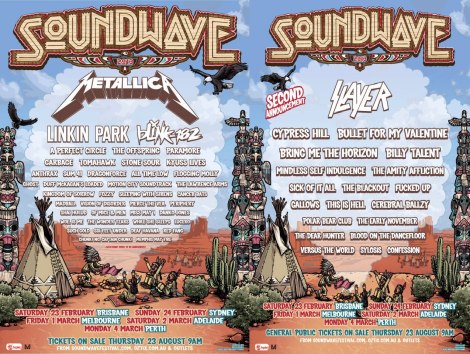

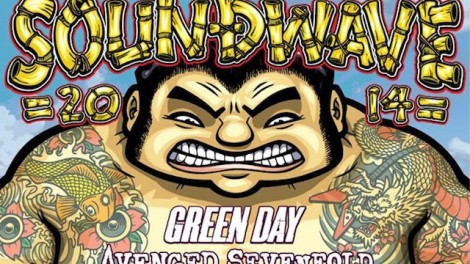

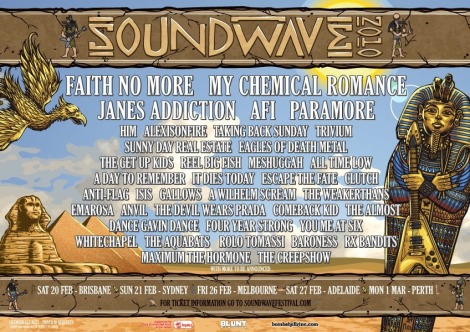

Each year Soundwave festival chooses a new theme for its poster artwork, and lead-in advertising and promotional material. In recent years, the festival posters have depicted the following:

* 2014: sumo wrestler with traditional tattoos (Japan)

* 2013: Native American campsite, complete with headdresses, totem poles, teepees, smoke signals and the sacred eagle symbol (Native American)

* 2012: Gladiators, marble columns (ancient Rome)

* 2010: pharaoh sarcophagi, pyramids, the Sphinx (ancient Egypt)

* 2008: martial artists, hand fans, peace gates (Japan again)

As can be seen, Soundwave is no stranger to using artefacts, customs, clothing or rituals from other cultures as the basis of its own promotional material. However, often the festival often goes further in appropriating foreign cultures – for example, a regular event in 2013 where fans could pose questions to bands on the lineup was called ‘Pow Wow,’ named after a Native American traditional gathering. In 2014, the series was called ‘In The Ring,’ in reference to a sumo wrestling ring.

Sacred Native American eagles, totem poles and war bonnets; actual Egyptian gods Anubis and Thoth, and Egyptian pharoahs bastardised and Photoshopped to hold guitars and drumsticks; Japanese peace gates, akin to those displayed in the Hiroshima peace park; all these and more have been co-opted, in cartoon form, on Soundwave posters in recent years without even a peep about cultural appropriation.

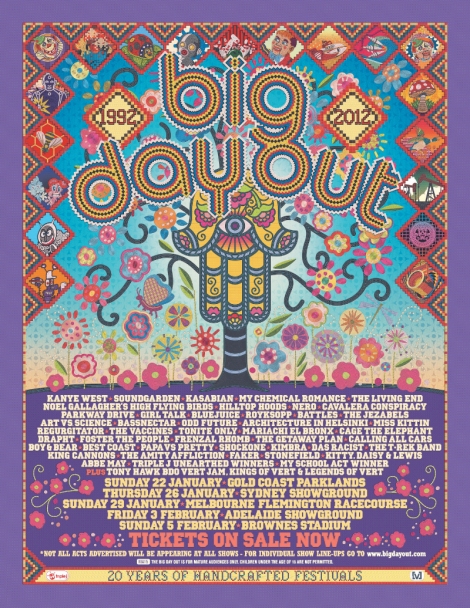

BIG DAY OUT

Big Day Out rarely has a such a defined “theme” to its promotional material, but it is still not totally guilt-free in the cultural appropriation stakes. In 2012, posters featured the image of an inverted hand with an eye in its palm – the symbol is known as a hamsa or the Hand of Fatima, and originated as a symbol or amulet of protection in Middle Eastern, northern African and Jewish cultures.

The symbol can be traced as far back as ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq) but now adorns the lower backs and upper necks of many young women worldwide in tattoo form. The symbol was traditionally thought to give protection and to ward off the ‘evil eye.’ The symbol of a flat palm with an eye at its centre is thought to predate even Islam and Judaism.

FUTURE MUSIC FESTIVAL

Future has had a few themes co-opting rich cultural traditions. This year’s festival theme was spruiked as ‘safari,’ but it had less to do with stuffy Englishmen in khaki suits holding blunderbusses to gun down curious elephants than it did with purely co-opting ancient (and stereotypical) African symbols. Tribal shields, savannah plains, arrowheads, nose piercings of bone, shrunken heads and feathers all featured prominently on the festival poster, which urged festivalgoers to “get your brave on.” Future called itself a” rumble in the jungle.”

The 2014 website is still live, and is a goldmine of cross-cultural confusion. A news post about the release of the festival timetables calls the news “totes Amazon-balls” – because when you’ve built a whole festival around co-opting African customs, why not throw in a casual reference to South America? Animal print is splattered across the page with phrases like “Tiki travel,” “claws out game on” and “Sahara survival guide” are plastered around. Instead of the standard links to Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Youtube, some comedian in the web team instead listed Toucan, Fiercebook, Instagrowl and Ewetube respectively. A ewe, or a female sheep, may not be the first animal you think of on safari, but let’s move back to the year before.

In 2013, Future Music Festival billed itself as ‘Day Of The Dead-set Legends’ – a take-off of Dia De Los Muertos, or Day Of The Dead. A Mexican religious custom said to stretch back up to 3,000 years, Dia De Los Muertos – October 31 – is the day when families pray for and remember deceased family and friends. Traditionally linked with the creation of sugar skulls, and the leaving of grave offerings, it is one of the most solemn days of the Mexican calendar – fitting, then, for it to become the central point of Future’s marketing in 2013. A giant sugar skull sits on the poster, surrounded by flowers, while the bottom of the poster reads “touring nationally March 2nd-11th 2013, muchachos.”

“Future Music Festival 2013 is going to kick harder than a Tijuana donkey on peyote!” screams some marketing material.

“Our Casa is your casa… This is the festivale de m sica futuro…Taco Taco muchachos!”

Lovely.

While we’re on the topic, a quick Google around finds Pyramid Rock festival in 2012 was themed around ancient Egypt, with a Sphinx flanked by a pair of pyramids (with added sub-woofers installed) above a “hieroglyphically listed” artist lineup including 360, Illy and Dead Letter Circus; Gosford’s Coaster festival in 2010 was all about the Native American totem poles; and Port Macquarie’s Festival Of The Sun in 2013 also had a Mexican theme, its poster populated by sombreros, skulls, maracas and ponchos.

And while we’re talking about this, is somebody going to do something about Empire Of The Sun’s future-tribal shtick? Feather headdresses, tribal warpaint, sacred eagles and images of the rising sun…. sound familiar?

I’m all for holding festivals accountable for decisions made that miss the mark, and Beyond The Valley’s usage of Native American tropes was over the top – but let’s not forget that the fledgling festival is far from the first to be guilty of that crime. The use of ancient cultural symbols by contemporary music festivals has been passing us by for years. Even with Meredith placing a ban on war bonnets, there is still a wealth of co-opted symbols that populate the Australian festival landscape; someone, please place Indian bindi forehead decorations on white girls at the top of the hitlist.